Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Last week, February 22nd rolled around. This was a significant date in the Cutler-Welsh household thirteen years ago when our house was located close to the Avon River in Christchurch. While it was a life-changing day for us, life has gone on. We ultimately lost our recently renovated home in Richmond as a result of the Canterbury Earthquakes, but many lost so much more.

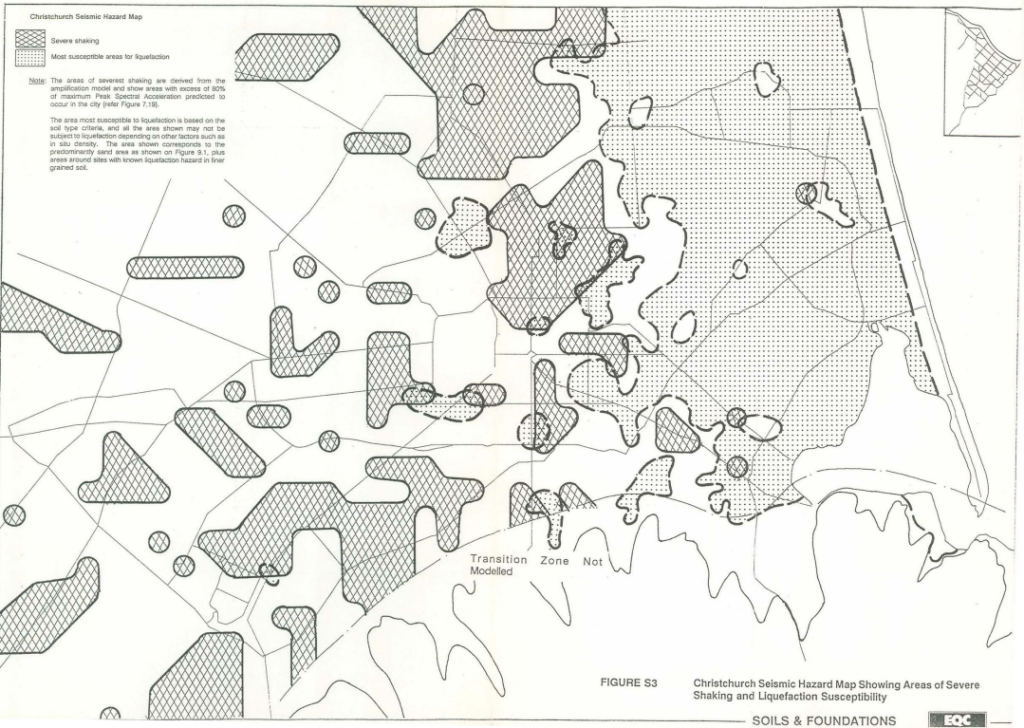

Thirteen years ago, I was five years out of engineering school at the University of Canterbury and the image of a worn, yellowing map hung in the geotechnical lab and passed by countless disinterested students, was still fresh in my mind. I remember a fellow mature-aged student pointing the map out to me one day and commenting, almost quizzically, how funny it seemed that we both owned homes in areas that could be prone to something called ‘liquefaction’.

Two things seem very odd about that sentence. Firstly, yes, two undergraduate students lived in separate homes that they actually owned, and secondly, not many people in Aotearoa at that time knew what liquefaction was. Most had never heard of it.

Perhaps I’ll go into the former point and the staggering rise in house unaffordability in a future post. For now, it’s increasingly important that we discuss where we should and should not be building homes.

The reason why my fellow student and I were not too concerned about our homes and our soon-to-be young families, despite the known soil conditions of where we lived at the time, was that Christchurch felt safe. At least safe from that particular hazard. In another course, we learnt all about the possible imminent danger of a tsunami destroying large parts of the east coast of the South Island. But liquefaction was only likely to occur with a big earthquake, and if that was going to happen, we felt it was much more likely to occur somewhere in the Southern Alps or Wellington. Not our problem.

It turns out, that geologists didn’t know where all the faultlines were, or where new ones might appear.

The consequences of the first round of earthquakes in September 2010 and then the tragically fatal quakes of February 2011, were massive. More followed later in Kaikoura.

Today, the side of the street we used to call home in Richmond, Christchurch is a reserve. It’s owned by the crown and I’m not sure the crown knows quite what to do with it.

Interestingly, the other side of the street still contains all the homes of our former neighbours. Courtesy of a fellow engineer who lived on our street (unfortunately for him, on our side of the street), we later found out why there was such as stark contrast from one side to the other. We had chosen a place to call home that was formerly a riverbed. Just metres away, our neighbours’ homes were about half a metre higher on what was formerly a riverbank.

Another indelible lesson from my time as a student of natural resources engineering is that rivers move. Particularly the type of rivers we have in much of Aotearoa. Braided streams carry huge sediment loads from their mountainous origins, continually depositing and sculpting the land. Natural banks form until enough sediment deposits to raise the bed of the river. When a large enough river flow occurs following a big rainfall or snow melt in the mountains, a stream might burst its banks and lay down a new course to start the process of sediment deposition somewhere else.

In this way, the Canterbury Plains formed over millennia within continually changing river paths.

Rivers moving around is not convenient for human settlement. We tend to like living near water, but we like the water to stay more or less in the same place. This is not how rivers work. Soon, it may not be how the ocean works either.

The largest river near Christchurch – the Waimakariri now snakes to the north of the city centre, currently meeting the sea at Kairaki Beach near Kaipoi. However, this has not always been the case. There is geological evidence that the path of the great Waimakariri once went through what is now the centre of Ōtautahi Christchurch to meet the sea via the Avon Heathcote Estuary and at other times, even further to the south forming Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere.

Earthquakes and tsunamis are inherently hard to predict. We can try and prepare for them and it makes sense to do so where geological and recent history shows us that it’s sensible to assume that it’s a matter of ‘when?’ not ‘if?’ they’ll occur.

Other events are slightly more predictable, at least in statistical terms. We can study the rate at which sediment accumulates in river beds. We can manage that particular risk by dredging the river and reinforcing the natural riverbanks with larger, more robust constraints to try and keep the water where it has become convenient and valuable for us.

Just this week we saw six suited politicians with shiny new shovels smile for the cameras as Hutt City embarks on a project to fortify the only thing protecting homes and businesses from the next large storm.

We can model the likelihood of a storm event of a particular magnitude occurring over a particular period of time. Hutt City got lucky in 2023 when the east coast of the North Island took the brunt of Cyclone Gabrielle. It’s now a race against time before the next storm arrives. (Fortunately, I think the contractors have bigger shovels than the politicians.)

Our family escaped the liquefaction of Christchurch and we’ve lived in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland since. At the time of writing, we are now one year on from a storm event that quickly became more expensive than the devastating Canterbury earthquakes. Once again, I count myself very fortunate. Some flooding in our garage and some photos lost due to my careless storage pales in significance to the price paid by others.

Where do we go from here? We know that similar storms, earthquakes, floods and fires will happen again. We have maps and models to show it. For the most part, we have a good idea of the areas at most risk of certain events, even if we don’t know the timing.

A big part of the dilemma is in part due to our desire to live close to water. Riverfront, lakefront and seafront property coincides with some of the most valuable real estate in the country, some of which is now becoming uninsurable. Yet despite this, we continue to allow the building of future homes and businesses in areas we know are susceptible.

The issue is far from black and white. What would a moratorium on consenting new buildings in known floodplains, tsunami or fire risk areas, look like? How would the resulting plummet in land values impact the economy and further inflate the cost of housing?

But if not now, when? The risks are likely to get higher and ultimately we have to ask ourselves if we’re prepared to keep making our stop-banks higher or retreat to higher, less shaky ground.