Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

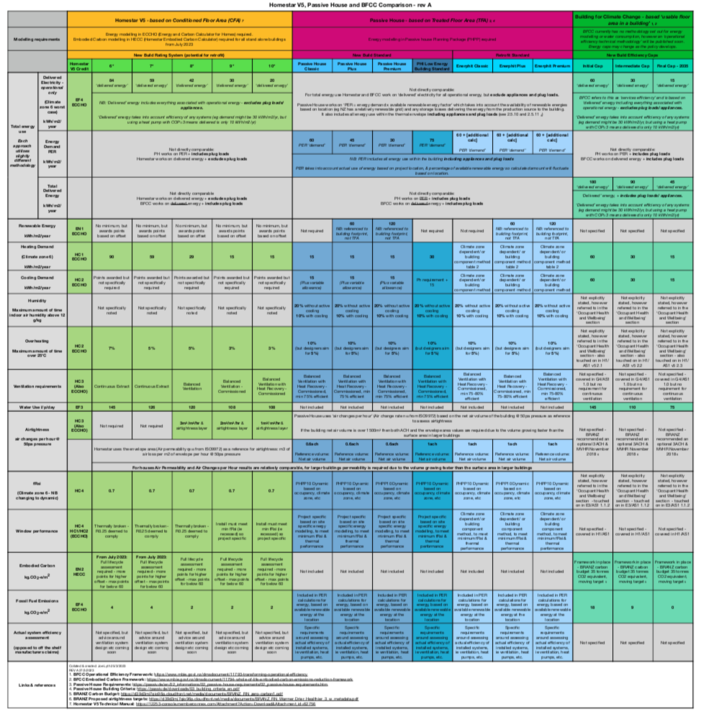

In March 2023, Homestar trainer, Passive House Designer and Certified Passive House owner, Joseph Lyth published a comparison of Homestar v5, Passive House and MBIE’s proposed Building for Climate Change framework. It’s a useful summary of these main three standards. There are other standards and brands out there, but these are the most relevant for new homes in Aotearoa. Except of course the main one – the New Zealand Building Code.

At the time of writing, there are over 8,500 certified Homestar homes in Aotearoa. The scheme is well established and well recognised with many leading builders around the country currently working through the details of how to achieve ratings under Homestar v5.

Passive House has been around internationally for nearly four decades in its current form, but present in New Zealand since about 2010 with the first Australasian certification being completed in 2012. New Zealand Certified Passive Houses now number in the hundreds. Jason Quinn’s library of projects is the most reliable source of certified projects.

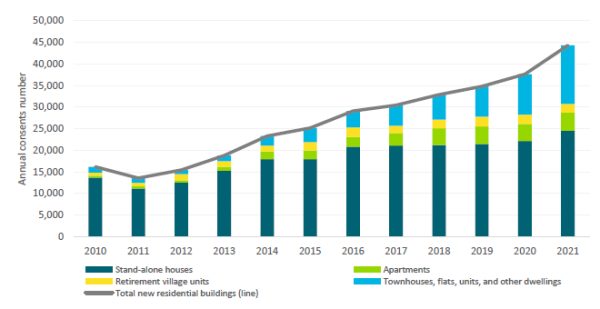

To put these numbers into perspective, there are now around 40,000 building consent applications for homes each year in New Zealand. There’s been some fluctuation over the last few years, but the order of magnitude is relevant.

The market uptake of Homestar in particular is encouraging. The 8,500 certified homes have not occurred evenly since the voluntary scheme was launched in 2011. There’s been a big uplift in recent years.

If we assume a current rate of around 5,000 Homestar registrations per year, plus a handful of Passive House projects, that leaves more than 80% of new homes in New Zealand that are only relying on the building code as a standard of compliance.

I use the term ‘compliance’ here carefully, because the building code, in my opinion, is not a standard of quality for two main reasons.

- There are fundamental gaps in what the New Zealand Building Code covers.

- The performance thresholds in numerous clauses of the code are not adequate to achieve the purpose of the code.

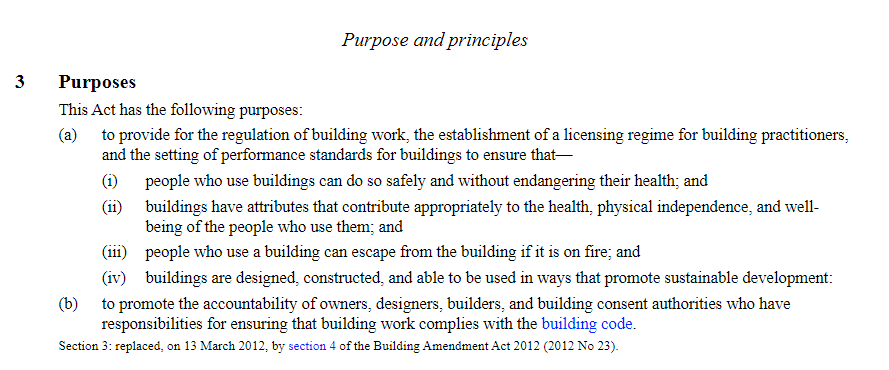

Like many Acts and laws, the Building Act has good intentions. The purpose and principles sound great.

The devil is in the detail (or lack of it).

Much has been written about the impact of poor housing on the health of New Zealanders. We have one of the highest rates of asthma in the world, we also have a high prevalence of mould in our homes. A case can be made that recent updates to the code have improved the likelihood of providing homes ‘safely without endangering health’, but this outcome is far from guaranteed.

And as for residential buildings that ‘promote sustainable development’, I don’t know of any clauses that address this.

The most significant deficiencies of the New Zealand Building Code that I’m concerned with are:

- Inadequate ventilation: Compliance with Clause G4: Ventilation is currently achieved simply by having some windows that open. This is proven to not be adequate.

- Moisture control: Thanks to ‘leaky buildings’, designers, builders and consenting authorities are very sensitive to moisture getting into buildings from the outside. This is addressed well in E2: External Moisture. E2 also has a smaller, often neglected sibling, E3: Internal Moisture which is quietly causing untold hidden problems.

- Overheating: The building code is completely silent on the risk of overheating. It’s not a new problem, but it’s getting worse.

These three reasons should be enough to justify the use of Homestar to inform the significant investment associated with building a new home. In 2023, the average cost of building a new home varied between $350,000 in the West Coast, to over $540,000 in Northland. When spending that amount of money on something, it makes sense to have an assurance that the product is fit for purpose.

Everyone wants to know about cost, which is a reasonable consideration when budgeting for a new build or a major refurbishment. The question is usually framed around the assumed ‘uplift’ in cost to achieve a higher standard of performance over that which is required purely for building code compliance.

A more useful frame of reference is to ask what the operating costs, health concerns and dissatisfaction will be from having a compliant but hot, stuffy and damp future home. The main message for consumers is that, unfortunately, building code compliance is not a guarantee of fitness for purpose if the purpose of your home is in line with those of the Building Act.

Joe Lyth was correct to include MBIE’s Building for Climate Change framework in his comparison a year ago because it provides a pathway to how we could achieve levels of performance in line with the purpose and principles of the Building Act 2004. With a new government in place, the implementation of the framework is uncertain. In the meantime, this increases the value of proven standards that take performance beyond the minimum or missing requirements of the building code.