Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Unless you live in a submarine your home is likely not waterproof. And that’s ok, as long as the majority of it is weathertight. To make something completely waterproof requires all sorts of seals and intricate design, often with second and third lines of defense against the pressure of water. Think sports watch or a fancy new smartphone.

There are parts of a house that should be made waterproof, for example underneath a shower well to stop water leaking down into the floor, and around a perimeter foundation wall that’s below grade to stop groundwater from seeping in. Another example is a flat roof where a rubbery type of material might be either painted or glued onto a substrate. But for the majority of a building, making it completely waterproof is not practical and often not desirable.

Hence the terms ‘weathertightness’ or ‘weather resistive’.

And Speaking of terms, we refer to a ‘WRB’ or weather resistive barrier, during our conversation. If you want to know your wraps from your barriers and everything in between, I recommend this article.

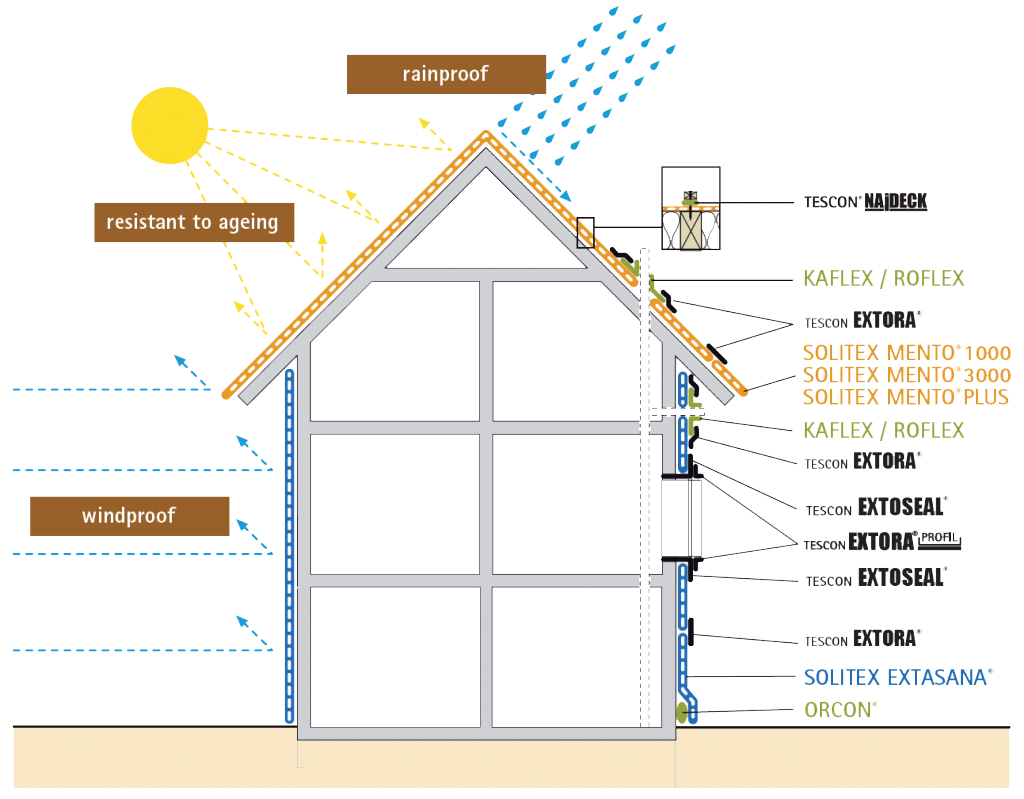

In a series of articles I co-authored with building scientist Jesse Clarke, we describe what we mean by weather. For the sake of protecting our buildings and the things inside them from liquid water, we’re mostly interested in the combination of rain and wind. We also need to consider temperature and relative humidity to determine how water vapour might behave.

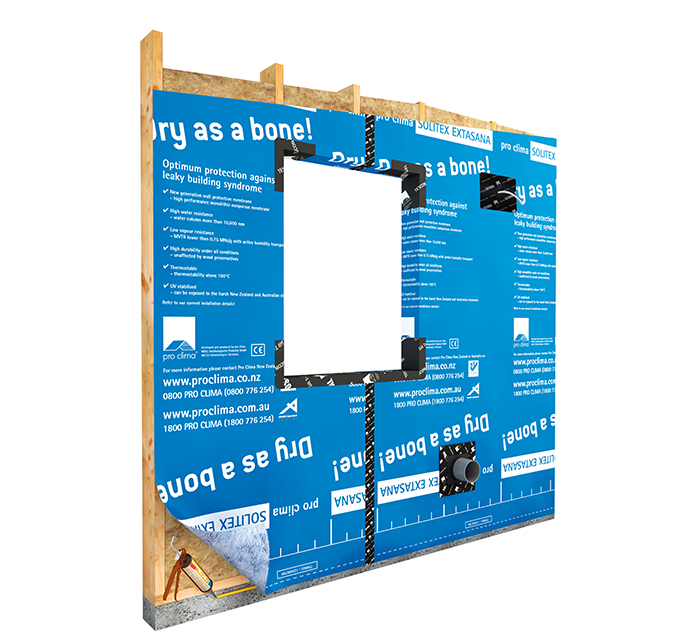

Following my previous chat with Simon Cator we continue our discussion about how to construct a good building envelope. This week we’re focussing on keeping the weather out. We cover the benefits of a monolithic membrane instead of a microporous one, the importance of being resistant to water while maintaining permeability to vapour, and how to keep everything connected.

For more detail, check out the product range and library of resources at pro clima NZ or Australia.