Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

In 2003, thermal performance requirements for residential buildings were added to the Building Code of Australia for the first time. The initial performance requirement was 4 Stars in the National House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) as simulated using the benchmark software AccuRate. In 2006, the requirement rose to 5 Stars, then to 10 Stars in 2010. This all sounds great. The increasing rating requirements of NatHERS provides a measurable and predictable target for improving the energy efficiency of Australian homes. But the building products industry wanted to know, how accurate is AccuRate?

From Store Design to House Design

Mark Dewsbury started out managing retail spaces where he learnt some tricks of the trade such as the best lighting and how to show merchandise to increase sales.

Influenced by his partner’s interest in sustainability, Mark built his own mud brick house in Glenn Innes, New South Wales. This added to Mark’s experience working with drawings and managing a construction project. It wasn’t a huge leap when he later studied architecture in order to fulfil the requirement of a qualification for work he was already doing.

Mark took three years of leave from working in construction and project management to study architecture at the University of Tasmania. He chose Tasmania partly due to the presence of sustainable design in the curriculum. In 2002 he completed a Bachelor of Architecture which he followed up in 2006 with a PhD.

While studying, Mark continued to consult and design. This eventually led to Mark’s private practice Carawah, which focussed on sustainable design and architecture.

Mark shaped the clientele of his architecture practice as much by who he turned away, as by which contracts he accepted. In this way, he quickly developed a name for himself as a passive solar and sustainable designer.

NatHERS

The Australian Government first proposed the concept of an energy efficiency star rating system for houses back in 1998. Energy efficiency regulations were then introduced in 2003 using a metric that CSIRO have been working on in the intervening time.

The National House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) is a design rating. It assesses the likely heating and cooling energy required for a house in one of 69 climates across Australia.

After the introduction of NatHERS, some organisations wanted to be sure that the software used to calculate ratings, was accurate. (Particularly pertinent as the most commonly used software is called AccuRate.) One such organisation was Forest & Wood Products Australia (FWPA). FWPA wanted to check if CSIRO had done their calculations correctly. They wanted to know if AccuRate was predicting fairly how timber performed in houses, compared to other heavier materials.

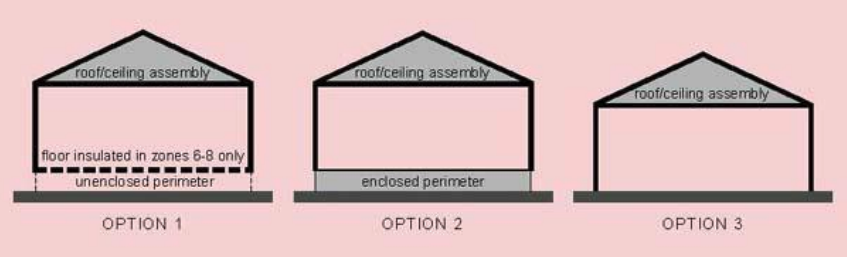

Originally Mark was going to use custom designed, fully autonomous, zero-energy houses to test the energy rating software. When this development fell through, they simplified the project to a set of test huts with different floor types and thermal mass. In parallel to this, a second project later compared code compliant and slightly above code houses.

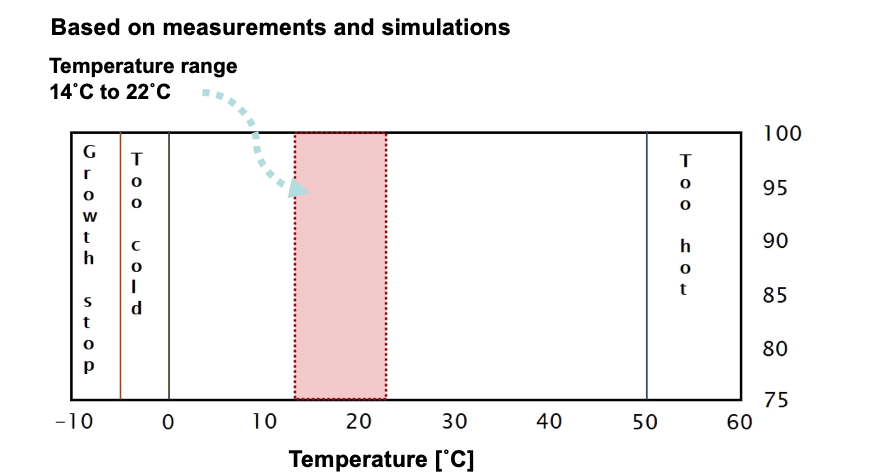

Mark and his team concluded through this research that the software did a reasonable job of estimating energy flows. The calculated simulations were found to be similar enough to the real-life measured energy requirements of the houses. Mark did conclude at the time however that further testing and calibration of internal temperatures would make AccuRate even more accurate.

Mark’s 2011 thesis “The empirical validation of House Energy Rating (HER) software for lightweight housing in cool temperate climates” is available through the University of Tasmania Open Access Repository.

Perverse Outcomes

When the Building Code of Australia adjusted to a 5 Star requirement in 2006, Mark saw an increase in the number of concrete slabs being specified. He says that this was an easy (and relatively cheap) way of achieving the slightly higher rating. Unfortunately though, the widespread and indiscriminate use of concrete has locked in a lot of thermal mass – often in the wrong place within a dwelling. Mark suspects this will make it very challenging to retrofit these homes to more stringent 7 and 8 Star requirements in the future.

Our Houses are Different

At the time of our interview, Mark was visiting Auckland along with Prof. Dr. Hartwig Künzel who was on sabbatical from Fraunhofer Institute in Germany. I asked Mark for his perspective on one of my ongoing themes which is, ‘how can we learn from experts around the world, instead of repeating their mistakes all over again?’

Mark pointed out that we do build differently, despite having similar climate zones. Australia uses a lot of double brick wall construction for example. New Zealand tends to use timber framing with a variety of light-weight claddings.

But regardless of these local preferences of construction materials, we’re facing similar challenges involving moisture control. We’re following the northern hemisphere by adding insulating for comfort and efficiency. Then we’re facing issues created by the introduction of thermal and vapour pressure gradients across increasingly airtight building envelopes. My frustration is that we seem continually surprised by these problems that have already been experienced and overcomes in Scandinavia, Europe and North America.

WUFI

Perhaps not surprisingly (after hanging out with the inventor), one of Mark’s suggestions is to use WUFI hygrothermal software for assessing the risk of moisture accumulation. This makes a lot of sense. Software like WUFI encapsulates much of that previous learning from the Northern Hemisphere, yet still allows us to assess our own building types and with our local climate data. Links

Links

- Mark’s profile page, the University of Tasmania

- Mark’s ResearchGate profile page

- Condensation in Buildings

- NatHERS

- AccuRate

Leave a Reply