Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

I recall visiting one of the fist 8 Homestar homes in Christchurch and being surprised that this new show home had a suspended timber floor. The double layer of insulation gave the floor a very impressive R-value, far better than any concrete floor slab I’d seen recently. All well-and-good, I thought. But thermally, surely it couldn’t be that great because it had no thermal mass. Right?

Later when I looked at the modelling numbers, I just couldn’t figure out how this timber floor house could, in theory, performed so well. Was this what I’d heard some experts describe as the ‘light and tight’ method of design and construction?

Since then, I’ve questioned the ideology of a concrete slab as the best floor. The theory of the all that thermal mass sounds good, but the devil is in the detail. Despite my research into the topic, I’m still yet to find the perfect insulated slab that leaves the concrete exposed as a useful and comfortable thermal flywheel (with the possible exception of MAXRaft now that they have an XPS option for more rugged edge protection).

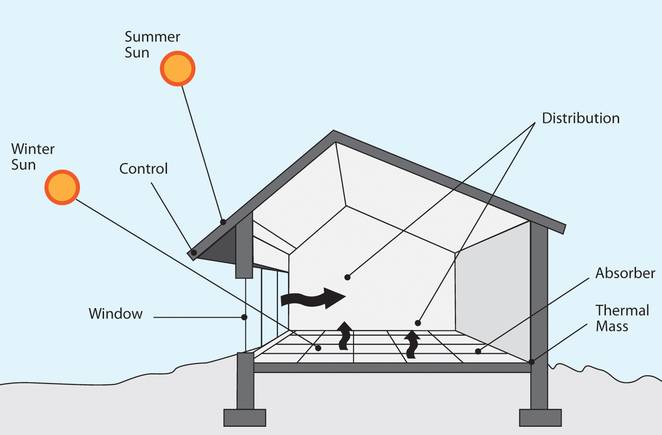

Trombe Walls and Other Thermal Promises

In other conversations I remember getting very excited when I first heard about trombe walls, only to have my dreams of the perfect passive heater dashed when a building scientist explained to me that he’d never actually seen a trombe wall work really well here in New Zealand, or one that didn’t just take up what would otherwise be a nice view.

And finally, there was my experience working under the hood of Homestar. I recall questioning the calculations that gave scarce recognition to any internal exposed concrete, brick or other heavy material that didn’t get anything but direct sunlight for a significant part of the day. This scientific assertion that only that part of the inside of a house (usually only the first 2 m of floor) that is hit by direct sunlight, will really contribute anything useful to passive heating, was hard for me accept. I wanted to believe that all exposed thermal mass must be good.

Local architect and fellow Homestar Assessor, Keith Huntington has similarly cautioned the dogma of thermal mass in his writings on eboss, which I also found jarring the first time I read it.

Everything I knew was probably wrong

So when I read Lloyd Alter’s headline on Treehugger – ‘Evertyhing I ever knew or said about green sustainable design was probably wrong‘, I knew that it was time to get some answers.

Does thermal mass matter, and if so how much?

And what about those all important eaves that I’ve ranted about in the past?

Passive House vs Passive Solar

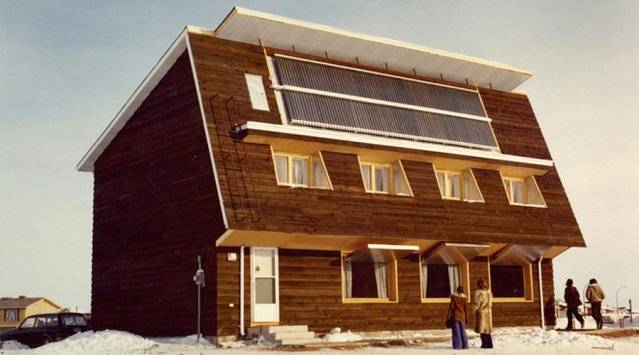

Much of this comes down to two design principles which are similar in name and have some overlap in their detail, but are fundamentally quite different. As Lloyd points out, the ‘Superinsulated’ house was really the origin and (along with airtightness) is the foundation of Passive House.

‘Passive solar’ design is what’s in question here, in particular the reliance on thermal mass and sun angles.

What Matters?

I don’t think passive solar design principle should be written off completely. It’s definitely good to design for the sun.

My main out take from this disruptive commentary is that airtightness really matters. I’m now starting to see the logic and potential of the ‘light and tight’ method of building.

Also in this episode…

Lloyd also makes mention of:

- Harold Orr, Passive House Pioneer

- The problem of price per square foot (metre) as a measure for homes

- Jevons Paradox

- HealthyHeating.com

Lloyd Alter

I highly recommend following Lloyd Alter. The best place to start is Treehugger. Then take your pick of social media and other channels from there.

Leave a Reply